- Home

- Jessica Day George

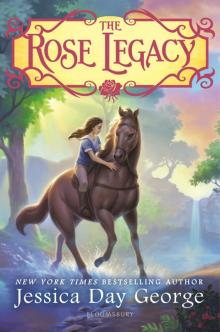

The Rose Legacy

The Rose Legacy Read online

To everyone, including myself, who ever sat on the arm of a sofa and shouted “Giddyup!”

To everyone, including myself, who tied a jump rope to the handlebars of their bike, and cried out, “Whoa!”

Also by Jessica Day George

Dragon Slippers

Dragon Flight

Dragon Spear

Tuesdays at the Castle

Wednesdays in the Tower

Thursdays with the Crown

Fridays with the Wizards

Saturdays at Sea

Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow

Princess of the Midnight Ball

Princess of Glass

Princess of the Silver Woods

Silver in the Blood

CONTENTS

1. Bad News

2. The Long Road North

3. Strange New World

4. Rude Awakening

5. Choking on the Truth

6. Head Stuffed Full

7. The Letter

8. Once Was Lost

9. Now Is Found

10. Dinner with a King

11. Bridles, Bluebell, and Bruises

12. Stiff Upper … Everything

13. Uncomfortable

14. Truce

15. Hiding with Florian … Again

16. The Owl in the Paddock

17. Another Letter

18. Council of War

19. Waiting

20. Reunion

21. Penance

22. Peace Mission

23. Faster and Faster …

24. Hunting Party

25. Red Silk Roses

26. The Royal Train

27. The Great Train Escape

28. Mighty Long Road

29. Mighty Long River

30. Horse Maiden

Acknowledgments

1

BAD NEWS

Anthea breathed on the cold window, fogging the glass, and wrote her name on the misty pane. Anthea Genevia Thornley. Jean, the upstairs maid, would have a devil of a time getting rid of the streaks, but Anthea didn’t care. Maybe Jean wouldn’t notice, and ever after when the window fogged, Anthea’s name would reappear.

Anthea had known it would only be a matter of time before she was shunted off to another set of relatives. Nobody wanted her for very long, although they were all very polite about it. It would not have occurred to them not to be, any more than it would have occurred to them to refuse to take her in. And it wasn’t as though she were a financial burden: her parents had left her a substantial inheritance. Somehow, though, she always seemed to be in the way.

She had lived with Uncle Daniel and Aunt Deirdre for three years now, the longest she had ever stayed anywhere. But Anthea could see in the frozen expression on Aunt Deirdre’s face lately that she was searching for some way to get rid of the unwanted girl.

“A new baby ought to do the trick,” Anthea muttered, her breath misting the glass to complete opacity. “At least I don’t have to stay on as an unpaid nurse.”

One of her mother’s cousins had used her as a maid of all work when she was hardly big enough to carry a coal scuttle. Anthea had been more than willing to be “sacked” for her poor silver-polishing skills. After that there was a second cousin whose son had pinched Anthea black and blue until she had slapped him in retaliation … and so on and so on.

Uncle Daniel was a dutiful sort who frequently apologized for not taking her in sooner. He had been the ambassador to Kronenhof for most of Anthea’s life. But when he had returned to Coronam and the city of Travertine, Anthea had been unceremoniously dumped on his doorstep. Aunt Anne had “put up with” Anthea for nearly a year, she told her brother bitterly, and wasn’t about to do it another minute.

“Oooh, Anthea! Jean’s going to be so angry with you!”

Anthea turned to see her cousin Belinda Rose standing in the door of the bedroom they shared, her navy skirt and sailor blouse still looking fresh and pressed and her eyes round as she looked at the streaks on the window. Anthea straightened her own blouse and then transferred the frown to her cousin.

“Are you going to tattle?”

“I might,” Belinda Rose said in a silky voice. “Or you could do my arithmetic …”

Anthea snorted. “I’d rather wash the window,” she said, putting her hands to her hips. “Go on and tattle! I’ll tell Aunt Deirdre that you were going to cheat.”

Belinda Rose put out her lower lip, pouting and thinking at the same time. “Oh, all right!” She flounced off. “Papa wants to see you in the library,” she called over her shoulder.

Grumbling, Anthea swatted at her own serge skirt, trying to restore the pleats. She was sure that her cousin had dawdled all the way so that Anthea would be scolded for tardiness.

Downstairs, Anthea knocked on the library door. The leather-upholstered book-filled room was her uncle’s sanctuary, and the children were only summoned within when they were in trouble. Which meant that, despite her best efforts, Anthea was summoned to the library at least twice a month.

“Enter.”

Anthea took her place on the Kronenhofer rug in front of her uncle’s desk. She clasped her hands at her waist and put her shoulders back, head high. She was trying for the exact pose depicted in the portrait of Princess Jennet that hung in the entrance of her school.

Uncle Daniel sat back in his large desk chair, his fingers steepled under his chin, and studied her. He did not seem impressed. Anthea sagged just a little.

Even though it was highly improper, she spoke first. “Belinda Rose has already told me the news.”

“I’m sorry, I didn’t want you to hear it from her first.” He frowned. “And I must speak to her about tattling.”

That gave Anthea a pang, since her cousin had just told her that she would not tattle. But then Anthea sighed, because it didn’t matter, really. She would be packed and out the door before Belinda Rose had time to think of a suitable revenge.

“At any rate, Anthea, I am sorry about this.” Uncle Daniel’s face was strained. “It’s just that Deirdre and I didn’t expect to have any more children. It has come as rather a shock, and necessitated a few … adjustments.”

“That’s all right, Uncle,” she managed to say.

She didn’t enjoy being lumped into the adjustments, which also included moving a cradle into Elizabeth Rose’s room. No one liked feeling like furniture. Anthea didn’t comment on that, however, but steeled herself to ask the question that was really troubling her.

“But where will I go? I thought I had exhausted the hospitality of every one of my relations by now.”

She grimaced. She didn’t mean to be a burden, but since no one wanted her to begin with, they were only too happy to find a reason to get rid of her. It didn’t seem to matter how good her grades were, or what awards she won, or how polite and eager to please she was at home. She was an inconvenience no matter what she did.

Her uncle gave her a pained smile. “Yes, er, that’s really what I wanted to speak to you about. There is, I’m afraid, only one other option.” He straightened the row of silver pencils on his desk. “It was Deirdre’s idea, which is surprising …,” he muttered.

Anthea crossed her fingers and silently prayed that the only option wouldn’t prove to be a spinster aunt who smelled of mothballs and liked to have the death notices in the paper read aloud to her every afternoon.

“You see”—Uncle Daniel cleared his throat and brought her attention back to him—“there really is no flaw in your character. You’re an amiable enough young lady, not without looks and charm … brains for certain. I wish Belinda Rose had half your … but no matter. Your father left you with ample finances as well, and I know you dream of taking up the Rose before you marry … a wort

hy goal indeed.” He paused, sighed, pursed his lips, and looked up at the ceiling.

“Then why does no one want me?” The question burst from her lips before she could stop it. She clenched her teeth to stop a sob from following.

Uncle Daniel, to his credit, didn’t bother to argue, but looked at her gravely. “Do you know what your father’s occupation was?”

The question took her off guard and stopped the tears before they could fall. “Not really,” Anthea admitted. “Actually, not at all.”

She had long ago deduced that her father had not been very highly placed in society. After all, everywhere Uncle Daniel went there were men who shook his hand and spoke in reverent tones of his work with the Foreign Office. But never once had Anthea encountered someone who knew her father.

Anthea drew herself up nevertheless and remembered that her mother would never have married someone who wasn’t of great importance. Before her marriage, Genevia Cross had been a Favored Rose Maiden. The queen herself had arranged the Cross-Thornley marriage.

“Your father managed his family’s estate,” Uncle Daniel said, his voice clipped. “It’s in a rather … unfashionable … location. Quite out-of-the-way, one might say.

“His brother, Andrew Thornley, is now the owner. He’ll be your new guardian.”

“I see.”

But she didn’t. She had never heard of Andrew Thornley, had not known she had an uncle on her father’s side, but Uncle Daniel had begun to speak again.

“He writes that he is thrilled to have you.” Uncle Daniel frowned down at a letter on his desk.

Anthea found this highly unlikely; no one was ever thrilled to have her. But it was nice of him to say so. It boded well for the next few months.

“You will leave in two days,” Uncle Daniel went on. “Your uncle will meet you at the train station outside the Wall.”

“The Wall?” One of her hands rose to the collar of her blouse. “Kalabar’s Wall? You’re sending me to live near the Wall?”

Uncle Daniel rolled his silver pencils beneath his palm. “Not quite. The estate is some distance beyond it, I understand.”

Anthea felt the ground heave beneath her feet. Her voice came out as a whisper. “Beyond the Wall? In the Exiled Lands?” Her knees were shaking as Uncle Daniel merely gave her a nod in answer.

Without asking permission, Anthea sank down into one of the high-backed leather chairs. The Exiled Lands! That was where the Crown sent traitors, pagans, and other undesirables! She had heard stories from the girls at school who came from northern Coronam. They said that the exiles ate unspeakable things, like raw meat and goat eyeballs. And the women wore trousers while the men wore skirts, but nobody wore drawers at all!

“I’m very sorry.”

Her uncle looked sorry. In fact, his face looked lined and almost old, though he was not yet forty. Anthea wondered how much pressure her aunt had put on Uncle Daniel to force him to send his niece into exile. And how dreadful a burden was Anthea that the only option left to her was to be sent into exile herself?

“Is my uncle—my other uncle—is he—” Her throat was so dry she couldn’t finish the thought, but Uncle Daniel knew what she was thinking.

“Andrew Thornley is not an exile,” he said. “He apparently chooses to live there. He says he will explain it to you when you arrive.” Uncle Daniel straightened the letter again, his mouth a thin line. “I am so sorry, Anthea. This isn’t something I would wish on any young lady of breeding. But I’m afraid that I’m rather at the end of my tether. Deirdre …”

He was saved from having to finish that thought by Delia, the downstairs maid, who bustled in, her eyes alight with curiosity. She would be dying to get juicy details about Anthea’s banishment she could carry back to the kitchen.

“Dinner is served, sir,” she said, her eyes on Anthea.

“Thank you, Delia,” Uncle Daniel said sharply.

With a disappointed huff, the maid backed out of the room. She valued her job too much, however, to slam the door or listen at the keyhole.

“You’re a good girl, Anthea,” Uncle Daniel said. “I’m sure that you’ll be all right. In a few years you can look toward a ladies’ college of some kind. There are none beyond the Wall, so you will be able to return to Coronam then. You might consider teaching, or nursing.”

“Either of those would be nice,” Anthea responded dully.

What was running through her head was that all she really wanted was to be a Rose Maiden, like her mother and her aunt Deirdre. But would the queen select a Maiden who had lived among exiles? Her heart shuddered.

She was ruined.

“Very good,” Uncle Daniel said. He seemed relieved, and Anthea realized that, after years of living with Aunt Deirdre, he’d expected her to have hysterics. “You’ll be back in civilized society before you know it.” He gave her a slight smile. “Anthea?”

“Thank you,” she managed.

“You are welcome. You may be excused.”

2

THE LONG ROAD NORTH

“Oi, Redge! You tosser!”

“What? I din’t do nuffin!”

“Tha’s the point! Mite of a schoolgirl in car two din’t get put out at Blackham!”

“I tried! Din’t her ticket say the Wall? Din’t it just!”

“Cor! Did it?”

“It did! Plain as brass!”

“Never heard th’like. She an exile, then?”

“Too young, in’t she?”

“Dunno.”

Anthea shut out the conductors’ voices with an effort. She opened her book, Lives of the Crown, and set it down again. Miss Miniver, the headmistress of her school, had given it to her as a going-away present. In her precise, angular hand the headmistress had written on the frontispiece: “Let these worthy examples guide you in lawless lands,” but Anthea wasn’t in the mood to read stories of piety and sacrifice.

She was restless, but there was nowhere to go, save up and down the narrow aisle of the train. But this activity seemed to be largely favored by men with cigars, and not young ladies, so Anthea didn’t dare to try it. Outside the grimy windows, field after field passed by, the monotonous green broken only by a quick glimpse of the occasional town or village. In the beginning there had been frequent stops at bustling stations, with passengers getting on and off and luggage being loaded and unloaded amid gusts of steam from the engine and shouts from the porters.

But everyone in her car had disembarked at the last station, and no one new had gotten on at all. The conductor had been shocked to find her still sitting there and demanded to see her ticket; he was certain that she had forgotten to get off somewhere farther south. There were no more stations left until they reached the Wall, where the train customarily delivered only mail before turning around for the long trek back to the south and civilized society.

Anthea breathed on the window and wrote her name in the foggy patch. Streaking windows with her name would be her way of leaving a mark on the world. Now that it seemed she would have no chance to leave a better one.

If she didn’t freeze to death in some hovel, as Belinda Rose gleefully predicted, then her reputation would be ruined. Permanently. Belinda Rose had been sworn to secrecy by her parents, but Anthea knew by the gleam in her cousin’s eyes that everyone at Miss Miniver’s Rose Academy would know Anthea’s fate within a day, a week at the most.

It was dark outside the train now. The green of the fields was gray and black in the moonlight, and Anthea could hardly tell the difference between a barn and a grove of trees. She opened the hamper at her feet and pulled out the last of the sandwiches that Mrs. Murch, Uncle Daniel’s cook, had packed for her.

Anthea ate the final sandwich—cold chicken with pickle—and drank the bitter tea. The cake was stale, so she nibbled the icing and candied cherries off the top and left the rest. Then she noticed something sticking out from under the napkin lining the bottom of the hamper. Lifting aside the napkin, she found a letter in what was unmistakabl

y Aunt Deirdre’s hand.

Anthea unfolded the note slowly. She wasn’t sure she wanted to be treated to a sermon on remembering her place or avoiding foreign customs just now. Something slithered out of the letter and landed in her lap, glinting in the compartment’s lamp.

Startled, Anthea looked at it for a long time before she realized that it was a silver pendant on a silver chain. And not just any pendant: a Royal Coronami Rose, set with a small pearl at its heart.

The Royal Family had ruled Coronam for a thousand years. Princess Jennet, the sister of King Aloster IV, had been the model of all that was good and lovely in a young lady. She had been not only beautiful but intelligent and pious, and so her symbol of the rose had become treasured by all young ladies who aspired to Princess Jennet’s example. Jennet had refused to marry so that she might spend her days waiting upon her sister-in-law, Queen Lythia, and had founded the Society of Rose Maidens.

Anthea had always admired the gold-and-garnet rose necklace that Belinda Rose had been given on her last birthday. Anthea set the letter aside and lifted this one. The silver rose was just as finely engraved as her cousin’s, and the pearl was a beautiful soft gray, which would suit Anthea’s gray eyes. She clasped it around her neck and resolved to try to live up to the example of Princess Jennet, no matter how dire her circumstances.

Then she picked up the letter to read.

My dear niece,

I am so desperately sorry for the grave trial that has been placed before you. But you have always been such a model of gracious behavior that I am sure you shall pass through this time and emerge unscathed, an example to us all.

And remember: if you ever have need of someone to confide in, please confide in me! I will anxiously await all your news.

Your doting aunt,

Deirdre August-Cross, R. M.

Anthea let her hands, holding the letter, fall to her lap. She hardly knew how to feel about this letter. Her doting aunt Deirdre? Anthea found her aunt’s letter very odd. Aunt Deirdre had never had a compliment for her when Anthea was living under her roof.

Frowning, Anthea read the letter twice more, then she folded it and stuck it between the pages of her book. She would worry about it later, she decided. For now, she had other things to occupy her mind.

Thursdays With the Crown

Thursdays With the Crown Silver in the Blood

Silver in the Blood Saturdays at Sea

Saturdays at Sea Tuesdays at the Castle

Tuesdays at the Castle Dragon Flight

Dragon Flight Dragon Spear

Dragon Spear Dragon Slippers

Dragon Slippers Princess of the Midnight Ball

Princess of the Midnight Ball Princess of Glass

Princess of Glass Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow

Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow The Rose Legacy

The Rose Legacy Princess of the Silver Woods

Princess of the Silver Woods Wednesdays in the Tower

Wednesdays in the Tower The Queen's Secret

The Queen's Secret Princess of the Silver Woods (Twelve Dancing Princesses)

Princess of the Silver Woods (Twelve Dancing Princesses) Dragonskin Slippers

Dragonskin Slippers