- Home

- Jessica Day George

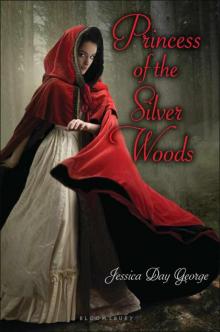

Princess of the Silver Woods

Princess of the Silver Woods Read online

Princess of the Silver Woods

Jessica Day George

Contents

Prologue

Traveler

Kidnapper

Kidnapped

Guide

Guided

Hidden

Guest

Witness

Chilled

Supplicant

Dreamer

Prisoner

Fugitive

Youngest

Worried

Assassin

Spy

Prayer

Conspirator

Gardener

Tested

Captive

Hunter

Dancer

Hero

Arsonist

Woodsman

Prize

Invisible

Petunia

Rescuer

Cloaked

Petunia’s Fingerless Gloves

Rose’s Baby Blanket

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Jessica Day George

For Amy Jameson, friend and agent

Prologue

“You promised us brides!”

“I grow weary of your whining, Kestilan,” said the King Under Stone. The king, who had once been Rionin, third-born son of Wolfram von Aue, gripped the arms of his throne, and the black stone made a thin cracking noise.

“Do you see?” Kestilan pointed to the throne, though no fracture was visible. “Our home crumbles around us! Something must be done!”

“Do you think I merely sit here night after night and gloat over my kingdom?” The King Under Stone’s chill voice would have done their father proud. “I am not blind.” The king gestured at the ballroom with a broad sweep of his long arm.

The marble floor had lost its sheen and there were shallow dips worn into it from a hundred thousand dances. The gilt was peeling from the mirror frames, and the velvet upholstery had faded from black and purple to gray and lavender.

Blathen murmured something, and the king’s head turned sharply. “What was that, dear brother?”

At first Blathen looked as though he would demur, but then he squared his shoulders. “Our father ruled for centuries, yet the palace was ever new,” he said again.

The King Under Stone nodded. “Very true. And you think that it decays now because I am not as strong as our father.”

None of his brothers moved or spoke, afraid to agree or disagree with this statement. Whatever his strength in comparison to their father’s, the new king could still kill any of them as easily as breathe.

The King Under Stone got to his feet, smiling as his brothers moved away. They stepped down off the dais, making him appear taller though they were all the same height. He took the opportunity to loom over them, and his smile became even more terrifying.

“I assure you this is not the case,” he said. “The truth of the matter is that the Kingdom Under Stone is dying because it was meant to contain our father, and our father is gone.”

“So we can leave?” Tirolian’s voice was rich with relief.

The king paused for a while, mulling over how best to tell his remaining brothers the news. “Not yet,” he admitted. “The kingdom is dying,” he went on at last. “Dying with us trapped inside. Like a birdcage smashed beneath a stone. The door to the cage is still locked and there is no way for us to fly out.” His smile became even more terrifying as he saw his words sink in.

“Then what do we do?” Blathen folded his arms across his chest. “I am not going to sit here and let the stone crush me.”

“Of course not,” the king said. “We need only to collect a few things to enable our escape.”

“And what do we need?” Blathen was still frowning, not convinced that his older brother had the answer.

“Just what Kestilan has asked for,” the King Under Stone said, sitting back on his throne. “Just what our father wanted for us: brides.

“Beautiful brides who can walk in the sun.”

Traveler

Petunia was knitting some fingerless gloves to match her new red velvet cloak when the Wolves of the Westfalian Woods attacked. She dropped one of her needles when she heard the first gunshot, and though she could clearly see the silver needle rolling on the floor of the coach, she didn’t stoop to pick it up. The bandits had surrounded them so quickly and so silently that she froze at the sound of the coachman’s rifle and the sudden halt.

“Put the gun down, my good man,” called out one of the wolves. “All we ask is your coin and any jewels, and you can be on your way.”

Sitting across from her, Petunia’s maid, Maria, began to cry.

Petunia pushed back the hood of her cloak, intrigued. No one had ever told her that the Wolves of the Westfalian Woods were young … but the voice clearly belonged to someone near her own age. An educated someone near her own age, unless she was mistaken. She retrieved her knitting needle and then tucked all four needles and the yarn into the basket on the seat beside her, pulling out her pistol as she did so. She checked the bullets, then cocked the weapon.

“Oh, Your Highness!” Maria was scandalized, but she had the good sense to whisper, at least. “Put it away!”

“They aren’t taking my jewelry,” Petunia said.

She owned only a few pieces—as the youngest of twelve princesses, she was hardly dripping diamonds and pearls. But what little she had was in a cedar jewelry case under Maria’s seat.

“They are not getting my mother’s ruby earrings,” she said. “Nor the necklace that Papa gave me for my sixteenth birthday. I’ve only gotten to wear it twice.”

It had a small ruby in the center of a petunia-shaped pendant, and the chain was made to look like petunia leaves. She would shoot anyone who tried to take it. She might regret shooting them later, but she would still shoot.

Hearing a sound just outside one of the coach windows, Petunia trained her pistol on it and braced her wrist with her other hand. She could see figures outside the coach—masked figures in the trees on either side of the road—but none clear enough to shoot in the twilight.

Then a face, the upper half covered by a leather mask made to look like a wolf’s head, poked through the coach window. Petunia carefully adjusted her aim so that the pistol was pointing at the bandit’s left eye.

“Give us your—Here now! Put that thing away!”

It was the one with the young voice, who sounded as if he were in charge. Petunia didn’t move.

“Now, Your Ladyship,” the bandit began. “No one will get hurt if you just give me your jewels and your money.”

“Correction,” Petunia replied. “No one will get hurt if you crawl back to your filthy den and leave us be. If you try to take my jewels, however, you will be very, very dead.”

“She means it,” Maria said, and Petunia was decidedly irritated by the dismay in her maid’s voice. “They can all shoot like men. A tragedy waiting to happen, I’ve always said.”

“Who can all shoot like men?” The bandit peered into the coach to see if there was anyone else inside.

“The princesses,” Maria said, before Petunia could shush her.

Petunia closed her eyes in despair, but only for a moment. She quickly refocused on the bandit, making sure that her aim was still true. She did not want the Wolves of the Westfalian Woods to know she was a princess. They would assume that she was loaded with gold and jewels, and they would not let her go until they had searched every inch of the coach.

“The princesses taught me how to shoot, when I was at court,” Petunia said hastily. “Though I am only the daughter of a lowly earl.”

“Only a lowly ea

rl’s daughter, is it?” the bandit snarled. “What a pity.”

Petunia refused to be fazed by the bandit’s sudden anger. He was no doubt hoping for better quarry, but that was hardly her fault. She inched the pistol forward until it was almost touching his nose.

“I can hardly miss from this distance,” she told him coldly. “Call off your men!”

The bandit had gray eyes, as gray as the dyed leather of his mask, which gave him a cold, wintry look. Petunia almost made a remark that wolves were supposed to have yellow eyes, but she didn’t think he would find it particularly amusing. It was more something Poppy would do, anyway. She concentrated instead on her hands, which were about to start shaking from the strain of holding the pistol still for so long.

Finally the bandit stepped back. “Come now, lads, it seems that this young lady is only the daughter of a lowly earl,” he called.

There were hoots of derision from the rest of the bandits.

“She can hardly have anything worth stealing, now can she?” their leader continued in his bitter, amused voice.

“Is she pretty?” asked one extremely large man, stepping into Petunia’s line of sight.

She promptly transferred her aim to him.

“Not bad,” countered the leader. “For an earl’s daughter.”

“Faugh!” There was the sound of spitting. “The only earl I’ve ever known was uglier than the backside of a donkey!”

The bandits seemed to find this the height of hilarity.

“Drive on, drive on,” Petunia chanted under her breath.“Why won’t you just drive on?”

None of the bandits that she could see were paying attention to their coach anymore. Was the coachman having the vapors? Maria appeared to be doing so, but Petunia couldn’t spare her much attention. Petunia released the hammer of her pistol and rapped on the roof of the coach with the butt, signaling for the driver to pick up the reins and move.

The coach moved. Not, however, in quite the way Petunia had in mind.

The noise of her pistol on the roof apparently scared the guard sitting on top of the coach, and he fired his rifle at one of the bandits. The bandit fired back, startling the horses. They bolted, dragging the coach behind them. There were shouts, and more shots fired, and the sudden lurching motion of the coach threw Maria off her seat and into Petunia’s lap. Petunia dropped her pistol, and her knitting basket fell to the floor, the contents spilling out and entangling her and Maria in red wool.

There was a scream from the roof of the coach, and then a thud on the road as the guard fell off. Maria, still on the floor of the coach, was now praying loudly.

Petunia tried to stick her head out of the window to see what had become of the guard, but she was thrown sideways, landing on top of Maria. The horses screamed, the coachman cursed, and they came to a halt with the coach tilted so far to the right that Petunia would have fallen out the window had it not been filled with earth and grass from a roadside bank, upon which they had apparently stuck fast.

She extracted herself from Maria, braced herself against the sloping seats, and tried to get the door open. She was short, but surely not too short to reach up and just—

“Allow me, Your Highness,” said the coachman, flinging open the door from the outside and making Petunia shriek in surprise. “Sorry,” he said, abashed.

“It’s all right,” she told him, when she had taken a deep breath.

She grabbed his forearm and allowed herself to be pulled up and out of the door, to sit on the upward side of the coach. The coachman stretched back through the door to pull out Maria, who stopped having hysterics long enough to clamber out with much groaning and panting.

From her vantage point, Petunia could see exactly what had happened: the road curved sharply to the left on its way through the forest. The panicked horses, going much too fast with a heavy coach behind them, had failed to make the turn and smashed into the high bank.

The other outrider was with the horses, soothing them. Petunia could see that one horse was severely injured, and another looked to be favoring a foreleg. She looked back up the road but couldn’t see any sign of the two-legged wolves or the injured man.

Petunia did not know what to do. She was not good with blood, preferring to spend her days gardening in the calm of her father’s hothouses. And as the youngest, she rarely had to make any decisions, her father having very strong ideas about what his daughters could and could not do, and her eleven sisters nosing in on anything that their father didn’t. The most drastic thing Petunia had done in recent memory was to have one of her oldest sister Rose’s old gowns remade into this cloak.

But now what to do? She was supposed to be at the Grand Duchess Volenskaya’s estate by nightfall, but the coach was broken, a man was hurt, and the horses were in no state to continue. Should she and Maria walk back to Bruch? Or should they wait for someone to find them? A shiver ran down her spine. The bandits had surely seen what had happened.

“Are there any estates close by?” she asked the coachman.

“None until we reach the grand duchess’s, Your Highness,” he said uneasily.

“What about an inn?”

“I’m afraid not, Your Highness.”

He, too, was scanning the forest for the bandits. He climbed down from the coach and went to confer with a guard who was removing the harness of one of the horses. The men talked in low voices for a moment, and then the coachman ran back along the road to the injured man.

“Should I go and help him?” Petunia called to the guard with the horses.

“No, no, Your Highness!” The man took an anxious step toward her. “You stay right where you are!”

Uneasy, Petunia clung to the side of the coach and looked inside for her pistol. It was there at the bottom among the tangle of her knitting basket. She felt an itching between her shoulder blades and knew the bandits were watching her from the trees.

“Allow me, Your Highness.”

One of the guards climbed inside and fetched the entire mess out, and Petunia distracted Maria from her fits by having the maid help her untangle the yarn and put everything neatly away, the pistol on top within easy reach.

“Now, just sit here and let the menfolk take care of matters,” Maria chided her.

Petunia tried. But sitting still, she was confronted with a more urgent question than whether to walk on or wait for help. She tried to ignore it, but by the time the coachman had helped the half-fainting guard back to the coach, she could no longer sit still.

“If you’ll excuse me,” she said, sliding down off the coach.

“Princess Petunia! Where are you going?” Maria squawked.

“Into the bushes,” Petunia said as casually as she could, while the coachman and the guards all opened their mouths to protest. “I’ll be right back, and I’m armed,” she assured them, tilting her basket to display the pistol resting atop her red wool, and then she climbed up the bank and into the underbrush before anyone could accompany her.

She did not need an audience to watch her relieve herself!

Kidnapper

Oliver sent his men back to the old hall by various routes, leaving only himself and his brother Simon to peer at the wreckage of the coach they had almost robbed. They took cover high up in one of the trees, on a platform concealed by branches and a few dead winter leaves.

“Does this happen a lot?” Simon leaned farther over the edge of the platform, and Oliver pulled him back before he fell.

“You mean, do we often cause people to crash their coaches?” Oliver couldn’t keep the irritation out of his voice. “No, we don’t!”

“I mean, one person points a gun at you and you back off,” Simon said.

Oliver spluttered for a moment, insulted. “That crazy little girl had a pistol one inch from my right eye, Simon!”

“She was a little girl?” Simon looked like he was going to make a smart remark, but the expression on Oliver’s face stopped him.

“I don’t know how old

she was,” Oliver snapped. “But she wasn’t very big, all right?”

“So was she small young or small little?” Simon pressed.

“Shush,” Oliver said.

The truth was, Oliver really didn’t know how old the girl was. Judging by the cut of her gown and her high-piled dark hair, she was in her late teens, but she was barely tall enough to look back at him through the high windows of the coach, and the hands holding the pistol had been just large enough to grip it. She also had the bluest eyes Oliver had ever seen, but that told him nothing.

Nor did he know why he had been so offended at her dismissing her father as being “a lowly earl.” Earls often held a great deal of land and wealth and enjoyed prime places at court. There was no need for her to be insulting about it, and toward her own father.

But there’d been a flicker in her eyes when she’d said it. Perhaps she was downplaying her family’s wealth and position in order to get away from him. The coach had been of good quality and so had the horses, before the crash, and she had a maid and three guards, plus the coachman. Of course, anyone traveling through the woods now had at least two guards with them, not that it stopped Oliver and his men from taking what they liked. Usually.

The combination of the pistol leveled at his eye and the girl’s insistence that she was only an earl’s daughter—though a friend of the royal court—had made Oliver hesitate. They had enough for now; they didn’t really need whatever the girl was hiding in her trunks. There was no harm in letting her go.

But then the horses had startled, and his men had barely had time to get out of the way of the stampede. A stray bullet had narrowly missed Simon, and then the idiot atop the coach had fallen onto the road. It rubbed Oliver’s conscience raw not to help, but Oliver had to remember that he was the villain and it was not his place to assist someone he had almost robbed.

Simon, he was sure, had been hoping to see some grisly injuries, but Oliver had been praying that the girl and her maid wouldn’t come to any harm. He would have stepped forward to help, then; he hadn’t sunk so low as to refuse an injured woman aid.

Thursdays With the Crown

Thursdays With the Crown Silver in the Blood

Silver in the Blood Saturdays at Sea

Saturdays at Sea Tuesdays at the Castle

Tuesdays at the Castle Dragon Flight

Dragon Flight Dragon Spear

Dragon Spear Dragon Slippers

Dragon Slippers Princess of the Midnight Ball

Princess of the Midnight Ball Princess of Glass

Princess of Glass Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow

Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow The Rose Legacy

The Rose Legacy Princess of the Silver Woods

Princess of the Silver Woods Wednesdays in the Tower

Wednesdays in the Tower The Queen's Secret

The Queen's Secret Princess of the Silver Woods (Twelve Dancing Princesses)

Princess of the Silver Woods (Twelve Dancing Princesses) Dragonskin Slippers

Dragonskin Slippers